|

Part

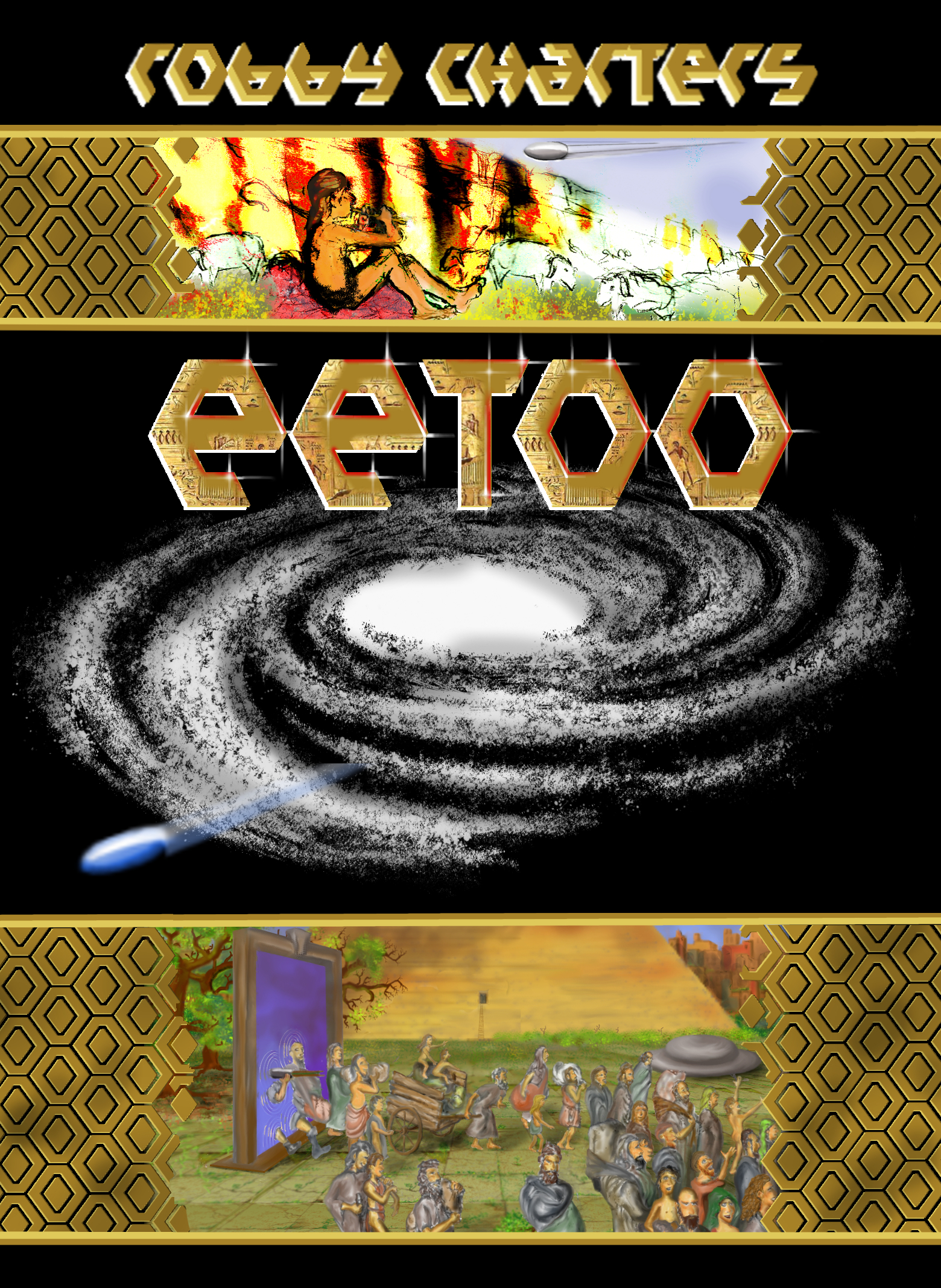

1 -- The Shepherd

1

nights

are dark on Klodi-Famta; there is no moon

not an orbiting body to

light the planet at night

nor

to interrupt the menagerie of stars

the galaxy thus visible in

obscured glory

the

shepherd boy sits beneath a tree

on a rise on the edge of a grove

he rests

surrounded

by grass plains, no living soul but the sheep

half a day's journey

from any human dwelling, he sits alone

the

sheep, one by one, go off to sleep

alone in the quietness of

night, his young eyes scan the sky

This

is the third time I've seen a light moving about in the sky.

The

first time, Uncle Zhue Paw told me it was only a shooting star. I

thought it went too slow for that, but I figured maybe he was right

and it was my mind playing tricks on me. Then I saw it again a week

ago -- definitely too slow.

Now

I'm positive it wasn't. Shooting stars don't stop and go back the way

they came. But they'd probably say I was lying. They already say that

knowing how to read the ancient writing makes my head too cloudy.

Oh

well, it's not bothering the sheep anyway. And they're probably

right. Lights in the sky don't do anything to people anyway,

especially this far from the village, so telling them would only make

more trouble for me.

I

might tell Venerable Too Dha, though. He's different from the others.

He takes me seriously, probably because he can read, and knows it

isn't bad for you. Uncle Zhue Paw would only scold me for being so

dreamy from too much reading.

Anyway,

I'd better get to sleep. It'll be a long walk back to the village

tomorrow. The sheep have settled down anyway.

There's

that light again, and now it's coming from that direction. Wouldn't

it be something if that were a ship -- like what our fathers arrived

on?

*

* *

Heptosh

scanned the surface once more, this time at an altitude from which he

could make out individual features. The all-around viewer, aided by

the infra-red sensor, showed the nocturnal landscape. The grassland,

the few clumps of forest here and there, looked dryer than Heptosh's

home planet, but well suited to keeping sheep. His activity shouldn't

raise any undue alarm from the inhabitants on this side of the

mountain divide. They'd mistake him for a shooting star.

Here

and there, he could pick out a shepherd minding his sheep, or a

caravan camped out for the night -- harmless, but it wouldn't be good

to interrupt their peaceful existence by suddenly appearing to them

out of the sky.

It

was those on the other side that worried him. They were a more

advanced civilisation -- or, at least they used to be.

If

they were as they used to be, they'd present no problem. The Klodi

and the Toki human populations had enjoyed many many happy

interactions.

Then,

they reported some sort of struggle. The Klodi had sent out a warning

not to enter their solar system until they had got their problem

sorted out. They also said something about seven transport shiploads

of refugees. It wasn't clear exactly what the trouble was, but the

refugees would explain it. So the sector council issued a

restriction, and waited. Then they went silent. No refugees ever

appeared. That all happened twelve years ago, as humans still counted

time.

Now,

the restriction had expired -- still, the silence, so Heptosh was on

a scouting mission.

So

far, he determined that on the Famtizhi half of the planet,

civilisation carried on as it always had. Heptosh had spend the last

several weeks making observations of life on the ground -- nothing to

worry about here.

But,

over the divide? He had detected no satellite surveillance, no

reconnaissance ships -- the Klodi hadn't been in the habit of

maintaining such a close watch, but who was in control now?

Whoever

it was, at least hadn't begun to guard the airspace. Perhaps that was

good.

But

perhaps it meant bionics. Bionics would follow the habits of their

human hosts, and therefore maintain the same level of surveillance.

There

were no signs of bionics on this side of the divide. He would cross

over and examine the ground on the Klodi side -- carefully.

A

mountainous isthmus separated the Famtizhi land mass from the Klodi

continent. Nestled in a valley in that isthmus, was the city of

Klodi, where he would find the space port. The mountains were quite

impassable for land travel, except for a tunnel through a mountain

from the Famtizhi area into the city, which was only approachable

from the rest of Klodiland via the subterranean portion of the city.

The same mountain range lined the North coast of the Famtizhi land

mass, surrounded the city, and then went along the South coast of

Klodiland. Therefore, access by sea was also all but impossible.

Heptosh

began flying at a low level across Famtizhi territory towards the

mountain range. His intention was to creep over in stealth mode below

the range of their scanners.

The

line of cliffs topping the mountain range loomed ahead of him,

running in a straight line as far as his eyes could see. A millennia

of erosion had rendered them more natural looking, otherwise, the

straightness of the formation was the hallmark of its human design.

Everything on these artificial planets, the mountain ranges, the

coastlines, even the caves under the ground, were done in straight

lines.

His

ship hovered in a cleft that had been eroded between two giant stones

forming the mountain range, providing him a vantage point. From

there, he looked.

2

a

fence encloses the mouth of the canyon

approach to the grass

within is through a gate

inside

is greenness, large rocks, a winding stream

the sound of a

waterfall echoes from deep within

outside

lies what once was a market

old stalls and stone tables tell of

bygone days

through

the gate the boy leads his sheep

into its safety he guides them,

replacing the bar

to

the abandoned shelters he then retires

he finds a resting place

among market stalls

tired

from the morning's walk, he sits

refreshing himself with the last

of his bread

They

say Fa-tzi-zhi, used to trade here with the Klodi. It must have been

exciting with so many people about selling things. I would have been

two years old when it all stopped, so I don't remember any of it.

The

sheep will be safe here until I come back with more food. I won't

stay in the village very long. I never do. Ever since Ni Gwah got

sucked down the whirlpool, Venerable Too Dha is the only close friend

I have.

I'll

visit him, and tell him about the lights in the sky.

I

wonder if it was the lights last night that prompted that dream?

It

was the same dream I've had before. I'm with someone in a dark cave,

holding a light. We find these golden plates that were buried in the

wall. The first time I dreamed it was when Paw and Maw were still

alive, and Venerable Too Dha hadn't started teaching me to read yet.

I must have been six years old. After that I started reading the

writings, and I read where it says there are golden tablets hidden

somewhere that will complete our knowledge, and it will be someone's

job to fetch them. Later, I had the dream again, when I knew it was

about those golden tablets. After I told Venerable Too Dha the dream,

he got all quiet. He still mentions it sometimes. I'm sure he doesn't

take it seriously,

I'll

ask Venerable Too Dha to let me read the tablets again. I've read

them so many times already, I wish there were more to read -- maybe

if someone found the golden ones.

*

* *

Heptosh

wasn't sure who introduced Bionic Replication to his native planet of

Nefzed. He was only old enough at the time to know it was the

in-thing for the rich and leisurely. Several renowned playwrights,

minstrels and storytellers had taken an implant. So had a few

senators' wives and other setters of the latest fashions.

They

placed it under the skin either in the forehead or in the wrist. It

was a chip containing microscopic bionic self-reproducing cells,

programmed to replace their neighbouring cells until the whole limb,

and eventually, one's whole body became bionic. When the process was

complete, there was the bionic humanoid, perfect in every way, with

super strength, super intelligence (so they said), absorbing all its

energy from sunlight, thus not needing organic food to keep it alive.

In fact, with proper maintenance, it would go on living forever.

For

all the advantages that were publicised, there appeared a sinister

downside.

Heptosh's

father, a university professor named Dr. Nashtep, was one of the

first to have major doubts regarding the process. Heptosh had

accompanied his father as a pupil and remembered the discussions they

had. One of his friends, a doctor, while closely observing the human

psyche during the last stages of the transformation, noted what he

thought were indicators of the death of the human personality that

originally animated the body. Others of their friends, including

other professors, doctors, art and literary critics, had also noticed

disturbing changes in the personality before and after. They became

convinced that the human soul did not survived a complete bionic

transformation. The bionic humanoid was no more than an artificial

intelligence storing the memory that used to belong to the soul.

What

was left was a good representation of a human personality, enough to

fool many. Playwrights and storytellers continued producing stories,

sometimes more furiously than ever. However, as time went by, and the

demand grew for new types of plots or literary styles, only

non-bionic human artists were able to adapt. Bionics couldn't keep up

with new trends.

Only

certain ones noticed this. The masses only continued following the

works of their favourites as long as they were popular. The fact that

they were bionic only seemed to enhance their image. They never

wondered, as the critics did, why they went from liking an old artist

to a newly bionic one. If anything, society put that much more

pressure on the more creative to accept a bionic implant. Refusal, in

some cases, put artists on a black list.

Those

who had undergone a complete transformation, the Total Bionics,

insisted that everything was fine. They voiced strong opinions that

they were the better for it, and did their utmost to influence yet

more people to become host to a bionic cell. As their numbers grew,

the dissenting voices became more and more marginalised. The Total

Bionics continued to gain political clout, and before long, there was

discussion about making a bionic implant mandatory for all citizens

of Nefzed.

Because

of the increasingly frequent food shortages, the idea of a body that

didn't require food, gained all the more appeal. The working classes

and the unemployed masses rallied for the legislation, which would

mean they would get their implant for free. Farmers weren't as

enthusiastic -- it would mean less demand for farm products -- but

even they began to accept it as inevitable.

Dr.

Nashtep and his circle of professionals formed the core of the

dissenting party. They spoke out as loudly as they could, but there

were backlashes. Mr. Takanen, a social commentator who had become a

close friend, made a final impassioned plea that was heard

planet-wide. Then he was soundly discredited, caricatured as a

crackpot, and banished from the media. Heptosh, himself, vividly

remembered the taunts by former playmates, the ostracism, the

betrayals by ones he loved; and at the same time, the fear for the

future -- his own and of humanity. Would he finally be forced to take

an implant? Would his soul die at such a young age? Would this mean

the extinction of the human race?

At

first, it looked as though all the dissidents could do now was to

ponder this question and wait for it to happen, or perhaps go into

hiding. A limited number were exploring other avenues.

One

of these included space travel. At first, that sounded like a pipe

dream. Even though most of the population was aware that space travel

existed, it wasn't an option that most thought likely. They knew that

humanity wasn't birthed on Nefzed. Humans had to come from somewhere,

and this presupposed space travel.

Dr.

Nashtep was the expert in history, so he knew that space travel was a

reality, only to be rediscovered. Once in Nefzed's history, a major

portion of the population had to be shifted to a new planet. That was

a long time ago, in the days of the ancient Nephteshi Interstellar

Empire. Then, they had the capacity to build mini planets out of

black holes. But that technology disappeared with the collapse of the

great empire. Their only legacy: hundreds of artificial planets

scattered throughout the galaxy, all populated to capacity. No one

was building new planets any more.

But

perhaps an empty planet wasn't necessary -- there weren't really that

many dissidents. Where there any friendly planets out there that

could take just a few more? They began to look at the options. Dr.

Nashtep's brother-in-law Nagasha, an engineer, spearheaded in this

operation.

They

had to be discreet, as some of the powers-that-be were opposed to

anyone seeking to leave. However, some of them were able to obtain

the information that was available.

Another

of their number, Mr. Vashkanen, had been a bureaucrat in the

planetary government, and had opted to take retirement before his

refusal to take an implant became an issue. Though bureaucrats and

academics had always been at odds, it was his concern about bionic

replication that brought him into their circle. Having once been high

up in the government, he knew things that historians, like Dr.

Nashtep, didn't. One of these was the fact that since the collapse of

the Nephteshi empire, interplanetary travel throughout the galaxy was

now regulated by the sector councils -- councils representing species

other than human.

The

council for their part of the galaxy, the Ziern Sector, was primarily

composed of Groki, a species that did everything in their power to

discourage human space travel. They had an extensive knowledge of

history, and some had even lived long enough to personally remember

the Nephteshi empire -- that it had been a thorn in the side of all

non-human species. The more they learned of the Ziern sector council,

the more it became obvious that the Groki were supportive of

mandatory bionic implants for humans. Other planets in the sector

were in the same position as they.

This

had never been a concern for most Nefzedis, as no one but government

people had ever though it necessary to do any space travel. The

government, knowing the perils, had always suppressed any ideas that

would lead to people venturing to try it. Mr. Vashkanen knew all

about that, and in his career days, was party to it.

But

this was a new day, with new dangers. Now, with Mr. Vashkanen's help,

Nagasha's people were able to find some unused ships powered by

logical relocators, the records of which had long faded from the

inventory books of the planet's bureaucrats. These kinds of ships

could simply relocate somewhere outside of the sector without being

detected. They also gained access to a galactic map, which showed

other sectors of the galaxy. Nagasha with a crew of four went off in

search of a friendly planet. Though they travelled hundreds of light

years, they kept in touch via twin particle communicators.

Tok,

though administrated by non-humans, offered the best prospect. The

governors of that planet were a non-Groki species that tended to show

sympathy toward humans. There was already a human community living

there quite happily, an Akkadi speaking tribe. The governors, when

they heard of the Nefzedi plight, extended them an invitation to

relocate a portion of their human population there. Other planets in

that sector were also found, with their help, and they sent giant

ships to help with the move.

The

exodus went on discreetly and took the bionic population by surprise.

All non-bionic humans who wished to move, gathered in a predetermined

location. They communicated their coordinates to the Toki ships that

were waiting in the upper atmosphere. They landed in stealth mode,

brought them all on board and sped them across the galaxy to their

new home.

That

was a long time ago, when Heptosh was young. Most of the elders,

including his father, Dr. Nashtep, his Uncle Nagasha and others were

dead. Only Mr. Takanen was left of that group, having lived to an

extraordinarily old age. Heptosh, himself, wasn't a young man any

more, though he remembered all of this as though it were yesterday.

Now,

the original home planet of the Nefzedi was wholly inhabited by Total

Bionics. No humans were left. Nefzedi humans were all living in the

Noofrishi sector of the Galaxy. Their Toki hosts allowed them to

administer their own affairs and they had relative freedom of travel

within the sector in which they lived.

Now,

perched in the cleft of the cliff overlooking Klodi City, he

wondered. Did the same fate befall Klodi-land?

3

simple

dwellings, the colour of the yellow brown earth

from which they

are made

further

on, yellow brown paths slope up the side of the mountain range also

yellow brown, except where interrupted by patches of green

near

by, small children run, their naked skin matching the yellow brown

earth both through dirtiness and natural colour

their

elders finish their chores, chat and enjoy the evening

as for the

smells...

I

can smell stew cooking behind Tee Maw's house. I hope someone has

enough food left from their family meal for me. Uncle Zhue Paw

usually has some but he always makes me wait until everyone else has

eaten. Venerable Too Dha usually eats by himself, so he might have

something.

Oh,

no! Here comes that brat, Nyu.

He

shouts, 'Hoi! Eetoo!'

'Aren't

you supposed to be studying?' I say.

'Hah!

I'm of age already! I can do whatever I want!'

'Of

age! You're not thirteen yet!'

'Of

course I am!' he snaps back.

'I'm

thirteen,' I emphasise to get it into his thick

head. 'I've just had

my manhood ceremony two months ago. You're at least a year younger

than me!'

'Count

the cycles around the sun! I'm thirteen!'

'Yeah!

Thirteen cycles around this

star!'

'What

other stars do you expect to go around!' He says it as though I

were the stupid one!

'Didn't

they teach you or what? Our fathers came from a different place:

different star, different planet!'

'Hah!

I think we've always been on this one!'

He's

so obstinate! 'And you expect to be the next Keeper of the Writings?'

I ask. 'You haven't even read them!'

'It

sure won't be you! You're just an orphan boy!'

'At

least I'm keeping up my family reputation of being a sheep owning

family. What are you doing?'

'My

Paw's got the biggest flock, and he has the respect of the whole

village.'

He's

got a point. I'd better not say anything stupid. 'Well, Ni Gwah

should have been it. He was better than both you or your Paw!'

'Hah!

The gods obviously didn't think so!'

He's

off in the other direction, muttering something extremely

disrespectful about Ni Gwah.

That's

another thing. The writings, which he thinks he's going to keep say

we must worship only one god. He still talks about the other gods

like the shaman of Tu-tu-ah does.

A

lot of people have got fires going. Mo Paw, the traditional wrestling

instructor is still at work making clay bricks. I think he's going to

build an extension to his house. I hope he leaves enough room for his

wrestling gym. Ni Gwah used to be good at that too -- always beat me

in wrestling.

There's

Wee Ta, still working away on her weaving loom.

I'll

need a new tunic soon. I hope this one won't start showing my

nakedness before shearing season. Now that I'm a man, no one gives me

any slack. I have to come up with raw wool before anyone will make me

a tunic. I might have to start going naked on days I'm far enough

from the village, so my tunic won't wear out so fast.

Cousin

Zhue is so shameless, he does that even when he's near the village,

in plain sight of everyone. He also eats most of the food at home so

there'll probably not be enough for a decent meal for me. Uncle Zhue

Paw never restrains him like he does me.

Venerable

Too Dha's all right though. He treats me like a family member, even

better than Uncle Zhue Paw. I think I'll go straight to his house.

There's

Doo Bweh, the baker. He sees me coming. I know exactly what he'll

say:

'Remember!

You owe me wool!' -- yep.

'I'll

remember,' I say on cue.

'Good.

Then come by in the morning for another dozen.' He's got the routine

down. I don't even have to put in an order.

I

pass by a few more houses and there's Venerable Too Dha, sitting on a

bench outside his door.

'Good

day, Eetoo,' he says.

'Good

day to you, Venerable Too Dha.'

'Come,

sit down and rest. How are the sheep?'

'They

are well. I left them in the canyon behind the old market.'

'You

won't leave them there many days, I hope.'

'No.

I just came back for more bread.'

'You

still have credit with Doo Bweh, the baker, I trust.'

'Yes.

I'll owe him three bags of wool, come shearing season.'

'You

have grown to be a responsible young man, Eetoo. Your father would be

proud of you.'

'You

flatter me, Venerable Too Dha.'

We

sit quietly for a while. He seems to be thinking about something.

I

think too, but about things Nyu just said.

'Nyu

seems to think he's going to be chosen to be the keeper of the

writings when you die.'

'Yes,'

he says, 'That seems to be the will of the village. But I'm afraid I

won't live long enough to teach him at the rate he's learning.'

'He

only knows the pictographs, and even then he says them in Fa-tzi-zhi

instead of the holy language.'

'Hah!

I remember you and Ni Gwah; I caught you two spelling out Fa-tzi-zhi

words using the Nephteshi phonetic letters.'

'Yeah!

You almost gave us a hiding!'

'At

least it showed you had mastered the language.' Has he got softer in

his old age? ' Ni Gwah was very good at it.'

'Yeah,'

I agree. 'Ni Gwah should have been the next keeper of the writings.

At least he worshipped only the creator god. Nyu still talks about

the lesser gods.'

'Yes.

It's a losing battle. Many of them, including Nyu Paw and Doo Bweh

Paw, went off to attend the spirit celebrations in Tu-tu-ah a few

days ago. At least they haven't tried to install a shaman here as

well.'

He

looks sad. After a pause, he says, 'I tried to persuade the council

at the last meeting, to make you the keeper -- that you were ready

even now -- but Nyu Paw seems to wield influence, and he wants his

son to be. Perhaps, unless I live to be very old, you can teach him

what he needs.'

'He's

such a brat, he'll never listen to me.'

'Perhaps

he'll grow wiser with age...' He's back to thinking again. '...and,

maybe it's better this way.'

'Why?'

'I've

been thinking a lot about that dream you had. I've had dreams of my

own.'

What

does that have to do with it?

'You

have a more important job,' he says. 'I've been wanting to tell you,

I haven't known how, and I fear time may be short.'

'What,

Venerable?' He looks healthy enough.

'Do

you remember what is written in the fifth tablet?'

'About

the seven laws?' I return.

'About

how Venerable Noka passed on his legacy to his three sons.'

'Yes.

He gave his eldest son the golden tablets, but to his second son, he

wrote it down on tablets of stone, and to his youngest, he wrote it

on animal hide. What we have are copies of the tablets of stone. The

original stone tablets were neglected by the Nephteshi guardians, so

Imhotep, the prophet-ruler, obtained them and added them to the great

library at Memphis.'

'Do

you remember what else?' he prods.

'Yes.

Some day, one from among the descendent of the second son must go to

read the golden tablets belonging to the eldest son so that our

knowledge of the Way will be complete.'

'I

believe the time is near when the descendent of the second son must

make his journey. That descendent is you. I am very sure of that.'

I

can hardly talk. I whisper, 'Me?'

'Make

your heart strong, Eetoo. I would not say it if I didn't believe it

were so. I've thought so for a long time now.'

'But

--'

'At

first, I dismissed it as an idle thought,' he explains. 'I tried to

forget it, but with time, it only began coming back stronger and

stronger. I discussed it with Venerables Zti Paw of Sho-ta-le and Meh

Zha of Nyu Pee River Village. They all feel the time is near, and

believe that my instincts are right. So, now, I must tell you.'

I

can't think of what to say.

'Rest

here tonight. Read the fifth tablet one more time. You must tune your

mind to the truth. I feel as though your journey may begin soon.

Perhaps even tomorrow when you leave here.'

'But,

where must I go to find the golden tablets?' I ask.

'That,

I don't know. There is much that I don't understand. That is why I

have delayed telling you, but tell you, I must. I've been troubled

about it in my sleep for a year now -- visions in the night. All I

know is, the tablets are not on this planet. They are near the

birthplace of humanity. Our people haven't travelled in the ships for

hundreds of years. They haven't been seen since before you were

born.'

'I

saw a ship last night -- or it was a light in the sky. I know it

wasn't a shooting star. And then I had the dream again.'

'There

you are, then,' he sounds more sure than ever. 'The hand of the most

high is already at work. You are the one. And don't worry about your

debt to Doo Bweh. If I don't see you again, I will repay it.'

We

have a meal of bread with a stew that Ae Maw brought by.

I

read the tablet.

*

* *

Heptosh

had observed as

much as he could from his perch in the cliffs surrounding the city.

He had use his magnifiers to get a closer look. He saw no signs of

life apart from a few herds of cattle. Perhaps some wrecked vehicles,

and -- bones? He didn't dare speculate. He still couldn't bring

himself to descend to ground level, at least not within sight of the

space port built into the mountains opposite.

Perhaps

with the information he had gleaned so far, the sector council would

see fit to send a larger investigation team.

He

used the linear propulsion motor to bring his ship into orbit before

engaging the logical relocator. The one had to be completely shut

down before it was safe to use the other.

The

first step was to simulate linear motion. That involved the reverse

beam transmitter sending a series of commands at very high speed,

each inducing relocation by half a hydrogen atom's width, thus,

pushing other matter out of the way instead of trying to occupy the

same location. Two atoms occupying the same space at the same time

can lead to atomic fusion, at worst.

It

also insured that the relocator was working properly. Not everyone

bothered to do that, but Heptosh believed in playing it safe. Only

one person he knew of had relocated himself to a totally unknown part

of the universe. By a miracle, he had managed to find his way back

with a faulty relocator and a good geographical knowledge of space.

Heptosh

set the relocator to simulated forward motion, and engaged.

Nine-hundred-and-ninety-nine

times out of a thousand it worked just fine. But this was that one

time out of a thousand that it didn't. The planet below him, instead

of growing steadily smaller, was jumping from one size to another.

He

flicked the relocator off. Using linear propulsion, he began moving

back to Klodi-Famta.

What

to do?

If

he travelled back to Tok using linear propulsion, it would take a

couple of centuries to get there. To him it would only seem like a

couple of months travelling close to the speed of light, but it would

be far too late to make use of the data he had gathered on the Klodi.

The

non-human species had other means of travelling beyond the speed of

light, but the only technology known to humans was logical

relocation, using the hyperspace coordinates to re-plot the location

of each atom within a given range.

So,

Heptosh's logical relocator wasn't working properly. He'd have to

land and try to get it fixed.

Was

it something he could fix himself? Where would he get help? Half of

the planet was primative. The other half -- what? Heptosh still

didn't know. Did he dare land there and find out?

He

was moving at a linear speed that would get him there in half a day.

He had time to think.

4

the

shepherd returns

the sheep sense relief

he

sits on an ancient seller's slab

and ponders...

So,

they say I'm the one who's supposed to find the golden tablets.

Venerable Too Dha talks like I have to go right away! How does he

think I'm going to do that? It's not on this planet, and I can't even

go everywhere here, much less anywhere else!

I'm

hungry. I'll have a piece of bread with some goat's milk cheese.

Tomorrow I'll take the sheep to the grass field near where I've

planted some gourds. There, I can pick some cucumbers and squash to

eat with my bread.

I

should start a small heard of goats so I can make my own cheese. I

wonder if I'll have enough wool left after shearing season to buy one

or two?

Hold

on! What's bothering the sheep?

They

see something, but whatever it is is behind those huts. I'll go

check.

I

leave my food on the stone table and walk about the huts near the

fence.

Oh

holy! It's a man -- dressed all funny! And I've never seen anyone

with hair like that -- it's grey, but it's in really tiny ringlets,

and his skin is real dark -- almost black! Did the Klodis look like

that?

He

sees me. I'm sure glad I didn't take off my tunic!

He

walks up to me and he's saying something.

'Shelta

pakh khalti'

Huh?

He's

saying it again, more slowly.

'Shel-ta

pakh khal-ti'

Part

of that sounds -- but no! The Klodi didn't speak Nephteshi. That's a

holy language!

'Shel-ta

pakh khal-ti -- khati Heptosh'

Khati

Heptosh -- That is

Nephteshi! It means 'my name is Heptosh'. Oh the gods! How can he be

speaking Nepteshi?

He's

saying it all again, this time using his hands to point and all that

sort of thing.

Ni

Gwah and I used to say things in Nepteshi when we didn't want other

people to know what we were talking about.

'Kha

ti Eetoo,' I say.

I

think I know what else he was saying: 'Can you help me?'

It

doesn't sound exactly like Nephteshi, but close enough.

'Nosh

ta, Eetoo,' he says.

That means, 'Hello, Eetoo.'

I

ask him if he is a Klodi.

He

says, 'No, I'm a Nefzedi, living on Tok.' He says it slowly, so I can

understand him. I have no idea what those places are, though.

He

talks faster than me, but he's got his sounds all wrong. That's why I

didn't understand him at first.

'I

need help with my ship,' he says. 'Does anyone near here know how to

fix a ship?'

'No

ships come here,' I say. 'I never see a ship.'

I

don't know if I have my tenses right or not. He understands me,

though.

'Come,'

he says.

I

follow him. We walk past the edge of the canyon, around the

protrusion and into the smaller canyon next to it.

That

must be a ship. It's a big round thing, like a covered dish, but with

legs. If he didn't say it was a ship, I would have thought it was a

giant's dish for cooking people in.

How

does he get the lid off?

I

stand there looking at it.

*

* *

Heptosh

looked again at

the shepherd boy standing with his mouth open. Obviously he'd never

seen a ship before. He looked as primitive as they come -- the

home-spun tunic that he could almost see through, no shoes, straight

rusty brown hair that might have been cut some months ago by placing

a bowl on his head, his question if he were a Klodi, probably never

met anyone outside his tribe. Did Heptosh really expect any help from

him?

But

the boy spoke Nephteshi! That was truly amazing.

Heptosh

probably would never have discovered that had he not been so

desperate. Maybe there was hope.

'Have

you never seen a ship like this?' he asked.

'Have

not,' said the boy.

'Do

you know who has seen one?'

The

boy only shook his head.

Heptosh

hadn't expected him to say yes, but he didn't know anything else he

could ask. But maybe...

'Do

you know the way to the land of the Klodi?'

'Yes.'

The boy pointed back towards the abandoned village.

'Can

you take me there?'

The

boy stared at him for a moment with his greenish eyes, and then said,

'Come.'

Heptosh

followed him back to the village, and then towards the rail fence.

'Many

years ago, the Klodi come here, they buy, they sell. Fa-tzi-zhi come

to trade. They stop. Now, nothing.'

'What

happened to the Klodi?' asked Heptosh.

'They

stop coming.'

'Why?'

The

boy shrugged, 'They stop.'

The

boy, Eetoo, lifted the rail that served as a gate. The sheep stood at

a safe distance, obviously wary of Heptosh.

A

winding stream flowed from inside the canyon, out past the village

where a stone bridge crossed it. The path Eetoo took crossed one of

the bends. He simply began wading in.

'Wait,'

called Heptosh.

Eetoo

stopped while Heptosh took off his shoes. The water came up to the

boy's knees.

Carrying

his shoes, Heptosh followed. Perhaps he'd try to follow as best he

could barefoot.

Some

of the sheep followed at a distance, though on the other side of the

stream.

The

boy's feet were obviously well calloused from years of trampling the

countryside unshod. After they crossed another stream, Heptosh had to

put his shoes back on. The ground was becoming more uneven, and the

stream was now bubbling over the jagged rocks.

Soon

they could see the end of the canyon and the waterfall that fed the

stream.

The

boy pointed to a road built against the cliff. Now, Heptosh could see

it went all the way along the cliff to the village, probably leading

to the stone bridge.

All

this stumbling over rocks and wading the streams when a road went all

the way!

Heptosh

looked in disbelief, but the boy looked oblivious to the irony.

They

climbed a few rocks up the face of the cliff until they met the road.

It took so much climbing it would have almost been worthwhile going

back to the stone bridge.

The

path continued to climb until it brought them behind the waterfall.

There, they found a cave.

It

was dark inside. They'd need a light. It was also getting late in the

day.

'How

far is it to the other end?'

The

boy shrugged. 'Three furlongs.'

Not

far, but Heptosh preferred to make a fresh start in the morning.

'I'll

come back tomorrow. Let's go back. Can we take this road all the way

to the village?'

Eetoo

saw no problem.

They

went back that way.

5

the

two return by way of the bridge

they cross the stream to the

market

by

the stalls their path divides

the traveller to his ship

the

shepherd to the seller's slab

there,

he sits once more and muses...

What

will the stranger want next?

I

still didn't eat my lunch, and it's evening already. My bag is still

on the stone bench.

The

stranger's gone back to his ship thing. He's probably got food there.

I

should have offered him some of mine. He is a stranger, and we should

show hospitality.

But

he's gone now. I finish my food.

I

wonder if that's the same ship I've been seeing?

It's

still light. I walk over to where the ship is. I don't see the man. I

sit on a rock and look at it.

I've

never seen anything like it. Where did the man go? He must be inside,

but I don't see any way to get in.

Is

this the kind of ship that goes to the stars? Maybe our ancestors

came on them.

It's

getting dark. I get up and walk back to the market. I put my stuff

into one of the huts and roll out my rug. I hang up my tunic to air

out, take my blanket and settle down.

I

can't sleep. There's so much happening.

I'm

still thinking about Venerable Too Dha's strange words. I have to go

to find the golden plates. He doesn't have any idea how, nor do I.

Our people haven't travelled on the ships for hundreds of years.

But

today, I've seen a ship, and I met the man that keeps it. I showed

him to the cave.

Perhaps

I can go on his ship to the stars, and then I can find the golden

tablets.

He

seems a nice man. I'm sure he'll take me. I'll ask him in the morning

as he goes to Klodiland.

He

even speaks the holy language for every day conversation! He's

probably one of the gods.

*

* *

Heptosh

flicked on his viewer. The whole upper dome of his ship turned

transparent, revealing that it was morning .

The

first thing he noticed was the shepherd boy sitting on a nearby rock,

gazing at the ship. To the boy, the ship would have looked no

different than before, as it was a one way viewer.

Interesting

young chap. Knows Nephteshi, though not very fluently.

Heptosh

hadn't heard that the Famtizhi understood Nephteshi. The Klodi only

used Nephteshi as the language of interstellar communication.

Wonder

what he wants now?

The

look on the boy's face gave no hint. He didn't look as though he were

in any hurry. Maybe it was idle curiosity.

Heptosh

decided to have his breakfast before emerging. He reached into one of

the compartments and got one large corn wafer and a jar of honey.

That would do for breakfast.

Corn

wafers were ideal for interplanetary trips. Some were made with

various fillings, such as meat or vegetable, or perhaps something

sweet. For breakfast, Heptosh preferred a plain one with honey.

The

boy just sat, perfectly still.

I

wonder if I couldn't use a helper for this excursion? Though

Heptosh. The boy looked as though he'd be no trouble. He seemed to

have the time for it.

Heptosh

had no idea what he'd find on the other side of the divide besides

the landscape he had seen from the cliff. He wasn't as young as he

used to be. Perhaps it would be a good idea to have a companion.

Could the boy fight?

He

downed the last of his wafer, licked some honey from his fingers, and

reached for his flask of coourzt

beverage.

Usually,

three or four swigs of it did him for the morning, but today, he

lingered over it. He wanted to think a while longer over what he had

to do.

The

coourzt

berry was native to one of the Blilkin planets, but had been

introduced to most of the populations in the sector -- both human and

non. The Nefzedi traditionally drank wine or fresh juice on their own

planet, but since settling in Tok, they readily adopted the coourzt

beverage as their favourite. Wine was okay for digestion, or getting

drunk, but coourzt

could be taken more often and in larger quantities without the side

effects. They brewed it in a manner similar to wine, often with

various herbs blended in, but it was more of a stimulant. A few swigs

in the morning made the eyes brighter and made one feel better

prepared to face the day. It was also good for adjusting to different

day and night schedules by helping one stay awake when one needed to.

Heptosh

nursed his coourzt and deliberated.

He

knew that much of what was to be found in the Klodi area was

underground. The surface had shown him nothing.

Normally

there would be at least a few people on the surface. The fact that he

saw none, should mean something. So should the fact that the shepherd

boy had never met a Klodi, nor, apparently, knew what one looked

like. They were not a black-skinned race, like the Nefzedi. He said

the Klodi used to trade at this market, but had long stopped.

So,

what was he to expect? Was it safe to venture underground?

What

choice did he have? He'd have to live here for the rest of his life,

or until someone got curious as to why he didn't return and came

looking for him. That could be a lifetime. This wasn't a high

priority mission, or they would have issued him a twin particle

communicator. The Human Affairs department of the sector council,

administrated by humans, wasn't known for its efficiency.

He

began to gather various items and put them in a carry bag: a metzig

torch, some corn wafers, a water flask, his coourzt flask, a spare

loin cloth and toga, bedding, and a few items for personal hygiene.

He already had his utility belt strapped on, which had his distance

viewer, night goggles, balm, knife and a small dart-gun. Then he

twisted the release handle and pushed the door open.

The

boy lurched to his feet in surprise, then stood there, indecisively.

'Can

you go with me through the tunnel?' Heptosh asked in as simple

Nephteshi as he could.

'I

can,' said Eetoo.

'Good.

Let's go then. I might need your help.'

Eetoo

followed.

Heptosh

insisted on going by way of the stone bridge. Eetoo had no objection.

Though

Eetoo had tended to walk either in front or directly behind Heptosh,

here he began walking beside him. He looked as though he were wanting

to say something. He made several attempts, but seemed to give up

before he started

'Yes?'

said Heptosh, finally. 'What do you want to tell me?'

Eetoo

pointed in the direction of the other canyon. 'Boat?'

'Yes?'

'Go

to sky? To heaven?'

'I

-- er -- travel to the heavens, yes.'

'Planet

have golden tablets, where?'

'What

again?'

'Er

-- ' then without warning, the simple shepherd boy launched into a

spiel in a literary form of ancient Nephteshi: '"Noka

was the father of three sons, and after the waters subsided, he wrote

for them, the words of this account: for his first son, Sim-Hep, he

wrote it on golden tablets; for his second, Kham-Hep, he wrote in on

stone; and for his youngest, Yap-Phet, he wrote it on an animal

hide. The account, according to all three, is complete, but in none

of them is it whole. One among the sons of Kham shall one day journey

to the sons of Sim and receive from his sons the writings from the

tablet of gold. One from among the sons of Sim will one day journey

to the sons of Yap Phet, and give to him the message of the golden

tablet."'

Heptosh

listened in amazement. Obviously, the boy had been taught Nephteshi

as a means to read ancient manuscripts in the possession of his

tribe. The names sounded familiar. They were associated with a

legendary account of a planet that was engulfed in water.

Eetoo

went back to his broken Nephteshi: 'I -- son of Kham-Hep. I must

travel find golden tablets of Sim-Hep.'

Heptosh

noticed he was looking at him, as though hoping for an answer.

'Who

told you that?' asked Heptosh.

'Er

-- ancient -- er -- old man Too Dha. He keeper of the tablets. He

have dream say I go.'

'How

do you plan to go?'

'Er

-- ' suddenly Eetoo looked perplexed, as though he were surprised

that Heptosh didn't already know. 'Er -- you Nephteshi speak -- you

god?'

'Oh

dear! No! I'm certainly not a god!'

'But

-- Nephteshi -- holy tongue! Men not speak to men!'

So,

Nephteshi was a holy language to his tribe, for reading their holy

writings. The fact the Heptosh spoke it made him a god!

'Nephteshi

is spoken by many peoples,' corrected Heptosh. 'On my planet, we

speak Nephteshi to people of other nationalities and other planets.

On the planet of Nephtesh, they have no other language to speak. They

must speak Nephteshi.'

'You

not god? But you have boat.'

'My

"boat" is broken. I must fix, repair, mend. If I were a

god, I could snap my finger and make it better. I cannot. That's why

I must go to land of Klodi.'

'You

carry me to planet of Nephtesh?'

'I

don't know where the planet is. I only heard it was the centre of a

vast empire once. And, my ship is broken.'

'Can

help me find?'

The

boy looked as though he'd break into tears if Heptosh refused.

'I'll

tell you what. You help me find parts for my ship. I'll think about

helping you look for the planet, Nephtesh. But what about your father

and mother? What would they say?'

'Father

and mother died. Only Uncle Zhue Paw, and old man Too Dha. I am man

now. I can go.'

Suddenly

Eetoo was no longer the shy timid shepherd boy of earlier. He was

someone with a mission.

By

now, they had reached the waterfall. Between the falling stream and

the cliff face, the road ended at the cave.

Eetoo

looked doubtful.

'You've

been in before, haven't you?'

'Yes.

Sheep run away, go in. I go in after. It night. I have fire.'

'Did

you find your sheep?'

'No.

I go and go, I hear sheep ahead, sheep afraid of light and go on. I

think road must stop, but go on. I want to go back, I afraid, but I

hear sheep. Then I see star light. Sheep gone. I wait for morning,

but then, no fire. Also, no sheep. I see Klodiland. I afraid to go

but I know I must not stay. Fa-tzi-zhi people must not stay. I go in

dark -- afraid.'

'I

have a light here.' Heptosh brought out his metzig torch. He lit it.

Eetoo looked at it in amazement. It lit the cave walls like broad

daylight.

'Ah!

Not afraid now!'

They

stepped into the tunnel.

'But

-- Klodiland dangerous for Fa-tzi-zhi people.'

'If

you are to go in search of the golden tablets, you will certainly

pass through places more dangerous than Klodiland.'

They

walked on and on. It was a straight rectangular passage with no

features aside from bare rock, and straight vertical seams every few

yards. Now and then, the passage made a slight angle. This prevented

any light from showing from either entrance, so it was impossible to

see how much further they had to go.

'How

much further?' asked Heptosh.

'Three

furlongs.'

'Oh

-- er, but didn't you say it was three furlongs all the way through?'

'Yes.

Three furlongs.'

'I'm

sure we've already been three furlongs. How much further?'

'Three

furlongs.'

'Then

that should be six furlongs.'

'Huh?'

By

the time Heptosh saw daylight showing around the corner, he estimated

that they had been seven.

He

shook his head.

6

the

valley stretches before them -- an ancient city, overgrown

avenues

and boulevards draped in shrubs and creeping vines

the

mountains that line the city, appear like giant bricks place atop one

another

the man-made landscape towers over the city

beyond

these, again, giant blocks rise into mountain peaks

forming the

geometric mountain range

This

is just the way I saw it before. Still don't see any people. It must

be okay. The Nephteshi man said it is. I can't believe I'm going to

go to the stars and find the golden tablets.

The

man is taking out something from his belt, putting it up to his eye,

and looking into it. He points it here and there. Maybe it shows him

things.

He's

looking at the mountain on the other side of the valley. It looks as

though it were made of giant bricks. There's a wide hole on the side

facing us that looks awfully big -- a lot bigger than this hole we're

in. A tree could easily stand up inside, and it looks as wide as the

mouth of the Nyu Pee river.

Now,

he's looking at the big square thing in middle of the valley, that

looks like a giant's house, made of the same giant bricks. I also see

normal sized houses here and there. Some are pretty big. There's a

road that leads from there, and a fork off to the mountain across

from us. There's lots of trees in between, and more houses.

Now,

he's trying to see where this path leads -- the one we're standing

on.

'Let's

go,' he says.

So

we start walking.

wide

enough for two to walk abreast, the path clings to the side of the

rock

it curves around what contours there are on the otherwise

straight range

further

on, the path doubles back

in three stretches, they reach flat

ground

It's

been a long walk. We're at the bottom of the mountain now, and

there's a road that goes off straight ahead. It looks like solid

rock. There's ivy growing on it in some places, and big cracks in

others where plants are growing through.

There's

a herd of cows up ahead going from one side of the road to another.

Some are stopping in the middle to eat the plants growing up through

the cracks.

There's

got to be someone about. Why would cows be wandering about like this

by themselves? Further off I see some horses, also loose by

themselves.

There's

a house, but it looks half fallen down.

The

man's looking about too. It looks as though he's as surprised as me

at not seeing anyone.

'Let's

go in here,' he says.

It

has an upper floor. We go to the big gate at the bottom. There's a

board missing. He looks in.

He

tries to open it, but it's locked.

Then,

he steps back a bit and gives it a hard kick. The door gives way.

We

go in. It's one big room downstairs.

The

back door is open. We could have gone in that way.

There's

a big thing in the middle. It has a couple of chairs built in, and

some handles and some sort of other funny things in the front, some

things with letters and crystal surfaces.

'A

(something or other)!' he says. 'I didn't think they were so

(something or other)!'

'Huh?'

I say.

'Have

you seen one of these before?'

'No,'

I say.

'It's

an (something or other).' He says it again.

Looking

at me, he says it again. This time I catch it.

'An

air scooter?'

'Yes.

It's been a long time since anyone's used it.'

In

another corner, there's a wooden cart, but part of it is rotted.

There's also some feeding troughs. I'm sure they had horses once, but

they escaped out the back door.

The

man looks at the ladder leading up to a door in the ceiling. He tries

the ladder to make sure it's safe. Then he starts climbing.

I

follow him.

I've

never seen so many cobwebs. The dust is as thick as my finger in some

places. I'm sure no one's been here in years. The room has chairs and

tables. There are some things lying about. He takes a stick and pulls

the cobwebs off, and dusts off some of the things. Some things, he

puts into his bag. One looks like a light, like the one he already

has. He's trying it out, and shining it on the rest of the room.

He

picks up a small flat box and opens it. There's no room to put

anything. It's just solid silvery stuff. There's a stick attached to

the lid, and he takes that and pushes it into the silvery stuff. He

waits for something to happen, but it doesn't. Then, he turns off the

shiny thing, opens it up and sticks the end into the back end of the

box. Suddenly the stuff starts moving, and little bits of it stick

up. I see they're all little tiny pins all stuck together. He pushes

some down to make letters, and other ones pop up, so he can read it.

I can tell they're pictographic letters in Nephteshi. It must be

magic.

He

turns about and sees me.

'This

is a (something-or-other).'

'Huh?'

'A

computer.'

He

shuts the lid and puts it in his bag.

'I'll

read it later. It may tell us a lot.'

He

opens a door to another room, but suddenly he shuts it again. He

looks at me, looking a bit pale.

'You'd

better stay out here, Eetoo.'

He

goes in.

What

does he see?

I

go to the door and open it a bit and peep in.

There's

a bed. It's hard to see what's there because of the cobwebs.

Oh!

The gods! It's someone's bones -- two people's! They're lying side by

side on the bed.

My

friend looks about and sees me. He tells me to go ahead and come in.

He

probably thought I'd be spooked.

He's

pulling the cobwebs off with a stick.

The

bones are a bit funny though. Some of it's not completely rotted. One

arm still looks it's still together, but it doesn't look like a real

arm. The man looks at me and says, 'Have you seen this before?' He's

pointing to the arm.

I

shake my head.

'It's

(something-or-other).'

'It's

-- what?'

'Bionic.

It's not real skin and flesh. It's human flesh that started to turn

into machinery. This is what I feared had happened. This also

happened on my own planet, and many families there also killed

themselves when they knew what they had done.'

Humans

turning into machinery?

'Let's

go,' he says.

We

go down the ladder again.

Now,

he's looking at the big contraption downstairs. He opens the gates on

both sides of the room so we can see it better.

He

turns some handles on it, and pushes on something, and waits. Nothing

happens. Now he's looking about the room. There's stuff all over the

place. He picks up this and that. It looks as though he's found what

he's looking for. It's a small box. He brings it to the thing, gets

down and opens a little door. He takes out a box that looks like the

one he found, and puts the other one in. He tries turning the handles

again. Something seems to be doing what he wanted. At least he's

happy about that. Then, he opens something else and does something to

another part of the contraption.

Then,

he dusts off the seat in front, and sits on it. He pulls a handle,

and suddenly there's a noise, sort of like a waterfall. Then, the

whole contraption lifts up into the air, about one hand's breadth

high.

'Get

on,' he says.

I

don't know about this. It flies!

'It's

okay. It won't hurt you.'

I

get in the seat behind him -- very carefully. The thing starts to tip

when I step on it, as though it were a boat.

I'm

sitting down. It's a nice chair.

Suddenly

we're going out the gate and back onto the road.

Wow!

We're going fast! Is it safe to go this fast? He said it would be

okay.

We're

going past more houses. Some cows run to get out of our way.

I'm

starting to enjoy this!

*

* *

Heptosh

kept his apprehensions to himself. The boy had no idea of the danger

that might lurk behind any corner.

Up

ahead were the remains of another air scooter. Bones were scattered

about.

This

time, there were whole bodies that looked bionic. One lacked a head,

and another had a hole in it's chest. The cavity looked burnt about

the edges. One of them looked as though its head had been burned off.

Heptosh

stopped the scooter, dismounted and walked over to the bionics.

What

could have caused this much damage to bionic bodies?

He

stepped to the wreckage. The bones looked as though they had been

undisturbed throughout the 12 year restriction. They were completely

dry, lacked any smell, one of the hands was bionic.

Wait.

What was the other one holding?

It

looked like a voltage shooter.

He

stooped to pick it up. It was a hand held tool that would draw the

voltage from whatever power cell was attached, and send a lightening

bolt to whatever you aimed it at. It could set fire to sticks, or

jump start a machine, or -- with a power cell this size -- kill a

bionic.

Clever!

How

much voltage was there left after 12 years?

Heptosh

aimed it at the wrecked vehicle. Just enough to produce a visible

bolt and make a black spot on the surface. Then it died.

It

also made Eetoo jump out of his skin.

'Good

weapon,' Heptosh said. 'We just need to find another power cell.'

The

boy looked at him blankly.

Heptosh

pointed to the bionics. 'Have you ever seen people that looked like

that?'

'No.'

Strange.

Apparently no

survivors. Perhaps they did a thorough job of exterminating them. But

some should have survived, either bionic or human.

He

wouldn't take any chances. He searched the wreckage for any spare

power cell. There were none. He put the shooter into his bag and they

got onto the scooter once again.

'What

people them?' asked Eetoo.

'They

used to be normal people,' began Heptosh. 'They took an implant -- er

-- a very small machine thing that can use what's in the body to make

more of itself. It reads the DNA and...'

Eetoo

looked blank.

'Well

-- it just makes more of itself until the whole body becomes bionic.

But the soul is dead.'

'Dead?'

'Just

a machine man without a soul.'

Eetoo

looked at the dead bionic once more with a look of dread.

Heptosh

started the scooter and they moved on.

They

passed more houses in various states of disrepair -- more wrecked

vehicles -- bones and bionic remains -- Heptosh searched a few of the

sites for power cells and other supplies. Another computer or two

would give a fuller account of what happened -- a tragic story, by

the looks of it.

Robbing

the dead wasn't Heptosh's idea of a good time, but if it would avenge

their death --

One

power cell seemed to have half a charge left -- probably enough to

disable three bionics if he set the voltage only moderately high. His

bag was weighing him down. If they had to do much walking, maybe

Eetoo could carry some of the items into his shepherd bag.

He

took a turn that he judged would take him to the pyramid. There

should be an entry to the underground infrastructure. All the

human-made planets had a similar architectural design, even if their

facial geography varied.

Though

they saw more wreckages and signs of battle, they stayed on course

until they came to the foot of the pyramid. Then, they circled it

until they found the entrance.

On

the side of the pyramid facing the space port he saw a lake --

rectangular shaped, but it didn't have a proper shore. Some dead

trees were sticking out of the water.

There

wasn't supposed to be a lake here,

thought Heptosh.

A

road led to the open gate through what appeared to be a park with

stone tables in the shade of some big trees. They stopped for lunch

before proceeding. Eetoo appeared to enjoy the corn wafer with

spinach and chicken filling.

They

entered the pyramid via a downward ramp wide enough for land

vehicles. From there, if Heptosh knew internal planetary

infrastructure, there would be a road straight to the space port.

He

and Eetoo mounted the scooter, Heptosh lit the lamps and they

descended the ramp.

He

turned to the left, the direction of the space port, but suddenly

found himself facing a rock wall.

He

turned to move along the wall to look for a door, but he found none,

only rubble and broken rock.

He

moved away from the wall, put the lamps on high power to get a better

look. What he saw took his breath away.

The

giant slab that formed the roof over the passage had fallen in,

blocking off the way to the space port. The two ends of the fallen

slab looked as though they had been blasted so as to make it fit

precisely into the entrance.

That

explained the rectangular lake up on the surface. The ground had

sunken in and filled up with rain water.

There

were other ways of getting in. Heptosh dimmed the lights, and started

down the other corridor.

Several

furlongs onward he came to one of the smaller doors into the central

area. It was shut, and there were stone beams placed into the

aperture, wedging the door in closed position. It was, in effect,

locked from outside.

What

about the entrance further down?

They

sped on to that. Same story. Were all the entry points to the central

area blocked off?

Suddenly

Heptosh knew. He also conjectured that if he were to go to the

surface, he'd find all skylights and vent holes likewise sealed.

Probably the entire population of bionics were trapped inside the

central area. Without sunlight, their primary energy source, they

would eventually go comatose.

It

was a good-news-bad-news situation. They probably didn't have to

worry about the bionics, but the only way to the space port now was

through the mountain range -- a long way. The scooter wouldn't be

able to navigate the whole route.

What

about approaching the space port from the surface?

If

he were a lot younger, he could have tried scaling the face of the

great wall to reach the space ship entrance. Eetoo could do it,

maybe, but how would he get Heptosh up?

They'd

have to go the long way. If they rationed wisely, the food would

probably last.

'Come

Eetoo. We have a long way to go,' he said.

7

sunlight

filtering from openings high above

illuminates stalactites and

stalagmites

that time has glazed over the human-hewn cave walls

the

sound of running water echoes through the caverns

the two trudge

on -- on foot

This

trip is really taking a long time. I'm sure the sheep will have

scoured the ground bare by now.

We

stopped twice to eat. His crispy bread is nice, but I think I'll go

back to my normal bread with cheese next meal. I'll offer him some.

We're

walking now. The 'scooter' thing won't fit through all these places

we have to go. We've crossed one underground stream.

At

least we don't need the torches on all the time, there's just enough

light coming through from up there.

I

can hear water up ahead. Probably another stream we have to cross.

There's also more light coming from that way.

Hold

on! I smell something cooking! There's a bit of smoke in the air.

Heptosh smells it too.

'Fish?'

he says.

Everyone

we've found so far is dead. Who could be cooking fish?

We're

up to the stream now. There's the mouth of a cave where the stream

goes out, and there I see a fire. Someone's sitting beside it -- a

kid, he's got no clothes on.

He's

looking at us, like he's scared.

Wait!

I know him! Ni Gwah? It couldn't be! He's dead!

He's

standing up. It is him! He's turning to run away.

'Ni

Gwah! Stop! It's me, Eetoo!'

He

stops, and turns about.

'Eetoo?'

'Ni

Gwah! How did you get here? We all thought you were dead!'

'I

think I am dead! How did you get here? Did you die?'

'You

look alive to me.'

'But

this is the place of the dead. Everywhere I go I only see people's

bones!'

'No.

It's Klodiland. All the Klodi's died or something. Some of them

started to turn into funny machine things, and they all killed each

other.'

'Who's

this man?'

'That's

Heptosh. He's going to take me to the Planet of Nephtesh to find the

golden tablets...'

'Huh?'

'..and

he speaks Nephteshi. Try talking to him.'

Heptosh

just stands there looking at us. I think he doesn't have any idea

what we're talking about.

I

tell him, 'This is my friend, Ni Gwah. He go down a -- er -- water go

around and round -- not come up again. We not find him. We think he

dead, but I find him here.'

'A

whirlpool?' says Heptosh. 'Ask him where he came down.'

Ni

Gwah understands him. 'There,' he says. He points upstream. 'Water

come down -- er ...' then he says to me in Fa-tzi-zhi, 'a long slide,

I thought I was sliding into hell. Then I landed in the stream and I

followed it until I came here.' Then he says in Nephteshi, 'Water go

whoosh!' He makes a motion with his hand.

Heptosh

looks like he knows. 'So,' he says, 'The head of this stream is in

the Famtizhi area. You must be a very good swimmer to survive being

sucked into a whirlpool.'

'Yes,'

I say. 'He very good.'

'How

long have you lived here now?'

'I

don't know,' Ni Gwah says.

'One

year,' I say.

'It's

been year?' he asks me in Fa-tzi-zhi.

He

takes us to the mouth of the cave. There are his fishes cooking on

the open fire. He turns one of them over.

Outside,

I see we're on top of a waterfall. Down there, there's a pool, and a

stream that goes on through a canyon. I guess it must lead into the

flat lands, but we see only steep cliffs from here. There's a

vegetable garden next to the pool.

'Did

you plant that?' says Heptosh.

'I

find herbs and plant garden,' he answers him. Then to me, in

Fa-tzi-zhi, he says, 'I found all sorts of vegetables growing wild

near dead people's houses. I take them and plant them here, so I

never have to go off and look at people's bones and stuff.'

I

can see beans, cabbages, a few gourds, and carrots.

Then,

he says, 'Come!'

He

jumps off the edge into the pool below.

The

water looks good. We've been walking a long way. I throw off my

tunic, put it beside the fire, and jump in myself. Heptosh walks down

the path on the edge of the cliff. He watches us for a while,

swimming and splashing. The, he carefully takes off his clothes and

gets in.

He

has a lot more to take off than me. There's a cloth he wraps about

his shoulders, and then a leather belt with pockets and lots of stuff

stuck in it, and then a cloth that he wears about his waist, and then

his shoes. Even then he's not totally naked. He's still got something

wrapped about his waste and strung between his legs, but I guess he

doesn't mind getting that wet.

We

have a good time in the water.

Heptosh

says we'd better spend the night here. Ni Gwah spears some more fish

with his stick, and cooks them for us. He's also made a blowgun, and

he says he catches rabbit and squirrel sometimes.

*

* *

Heptosh

looked about as much as he could in the morning light. The mountains

blocked any view and it would be a long walk to the mouth of the

canyon -- Ni Gwah said it was three furlongs. He was beginning to

suspect that Famtizhi people could only count up to three. He decided

that the best thing would be to continue through the underground

passages.

The

new boy, Ni Gwah, could come with them. They would get him home where

his parents and relatives would certainly be happy. Ni Gwah could

probably use some clothes. He'd obviously been sucked down the

whirlpool while swimming naked in the stream, and hadn't seen any

clothes since, except those draped about dead bodies.

Heptosh

fetched his extra toga from his carry bag and helped Ni Gwah put it

on. He didn't look bad in it, though it wasn't the sort of thing he

was used to wearing.

Then,

they were off. This time, their food supply included some cooked fish

and various vegetables from Ni Gwah's garden plot.

Later,

they lunched on some of Eetoo's bread and cheese, and some cabbage

and cucumber. The cheese tasted rather nice, Heptosh thought.

By

evening, they had entered an area with wider passages. The scooter

could have been useful here. They finished Ni Gwah's fish with some

of Eetoo's bread, and settled down for the night.

They

drifted off to sleep.

8

Heptosh

was abruptly awakened by a kick to his ribs. There were people

walking about, holding weapons. He heard a scuffle next to him, and

looked just in time to see a human figure grabbing a toga, while Ni

Gwah escaped its folds, running off in the direction they had come.

The

human figures -- three of them, Heptosh counted -- forced Heptosh and

Eetoo to their feet and they walked down the corridor in the opposite

direction from the way Ni Gwah escaped.

There

was a conveyance waiting for them. As soon as they were seated and

flying down the wide corridor, Heptosh tried to catch a glimpse of

their captors by what light was available.

It

was too dark. He could only see that there were three of them, plus

himself and Eetoo.

Good

luck, Ni Gwah, He thought.

Soon,

they came to a more well lit area.

These

were bionics.

They

came to a stop, and the bionics escorted the two off the conveyance,

up a narrow corridor, and into an office.

There,

they met a stout gentleman dressed in his human clothes, but with

bionic skin. Most bionics Heptosh had known hadn't bothered with

clothes after their transformation.

He

said something to the escorts, and they bowed and left the room.

'Don't

be alarmed, gentlemen. I have a glitch in my programming that

prevents me from pretending to be a self conscious living human.

Please sit down. Welcome to Klodiland. My name is Shan. That is, my

late human host was known as Shan, the son of Khong.'

Heptosh

sat down in one of the chairs. Eetoo followed his example. Shan also

sat down.

This

was unlike any bionic Heptosh had ever heard of.

'You

are confused, no doubt,' Shan went on. 'Before we succumbed to the

final stages of bionic transformation, the human Shan gave himself a

bio-media upload. Are you aware of that process?'

Heptosh

was aware. It was the only known process of uploading information to

the human brain. But it had a downside: anything input into the mind

in this way became extremely vivid, like a phobia, or an obsession.

It would be easier to jump off a cliff in ignorance of the law of

gravity than to unlearn something thus uploaded to the brain, so

unless great care is taken in the selection of information, an upload

could lead to obsessive behaviour or a neurosis.

'Because

the upload so vividly imprinted actual facts onto my brain which Shan

had carefully selected, it overrode the programming that was built

into the bionic chip. Whereas most bionics are programmed to portray

themselves as intelligent living beings, my understanding of the true

state is the same as that of my human host before the

transformation.'

'So

you actually found a creative use for bio-media upload!' commented

Heptosh.

'Indeed.

Oh! I'm sorry for being such a bad host. I haven't even asked you

your names!'

'Ah,

yes,' began Heptosh. 'I'm Heptosh, this is my young companion, Eetoo.

I'm afraid Eetoo hasn't been able to follow all you've said.'

'Yes.

From the Famtizhi area, I see. Their tribal culture is probably their

best protection from bionic take-over.'

'How

so?'

'Bionics

are incapable of cultural adaptation,' explained Shan, 'and therefore

would be unable to relate to their values in a way that would

persuade them to accept a bionic implant.'

'You

seem to understand it quite well,' said Heptosh.

'I

was programmed by the bio-media upload to learn as much as I can

about bionics, and to pass that information on to humans as soon as

the opportunity presents itself, as it has just now. Besides that,

I've been doing my original job of maintaining the internal

infrastructure of this planet until such time as humans arrive to

relieve me. Is that your purpose in coming?'

'I'm

only on a fact finding trip' replied Heptosh. 'I'm sure something

could be arranged later on, when the sector council has had a chance

to review all these facts. My biggest problem right now is getting

off this planet. My relocator engine isn't functioning properly.'

'Then

take my ship. I have no use for it.'

'You're

a life saver!' exclaimed Heptosh.

Heptosh

told him about Ni Gwah.

'I

was told there was another human. I'll send him on his way to the

Famtizhi area as soon as my bots find him. I do wish I had something

to offer you by way of refreshment. We bionics only consume

sunlight.'

'Oh,

don't worry about us. We brought plenty of food for ourselves.'

'So,'